When I moved to the USA, I was surprised to see so many old people (old, in the sense that they seemed well over ‘retirement age’) working the checkouts at supermarkets.

When I moved to the USA, I was surprised to see so many old people (old, in the sense that they seemed well over ‘retirement age’) working the checkouts at supermarkets.

I was told that it’s because they need the employer health benefits.

But, soon (if not already) it will simply be because they need the money.

Right now, according to Wells Fargo, 1 in 3 Americans between the ages of 25 and 75 believe that they will be working until they are 80 years old. Not because they want to, but because they believe they will need to.

And, they are correct.

Unless you can live on just 50% of your current paycheck, so that you can save at least 50% of your income for the next 17 years (or, save at least 25% of your income, if you’re happy relying on Social Security for the rest of your life), you will simply not be able to afford to retire.

And, there’s yet another problem with these ‘save your way to wealth’ strategies: they all assume that you’re actually happy living on your current after-savings income. Well, are you?

I didn’t think so 😉

That’s why I decided to fly in the face of commonly-accepted personal finance ‘wisdom’ and start blogging here …

I think that true personal financial planning starts with just two questions that you need to answer very, very honestly and carefully because they will set your whole Financial – indeed Life – Strategy from this point on:

1. How much income do you want when you begin life after work?

2. When do you want to begin life after work?

Together, these two answers will then direct you to everything else that you need to know:

How much do you need before you can retire?

This is called your Number, and is very easy to work out in two simple steps:

STEP 1 – Double your answer to the first question for every 20 years in your answer to the second question.

Let’s say that you decided that you want $25,000 a year income (in today’s dollars) in 30 years time. You would double that to account for the first 20 years ($50,000), and add another 50% for the next 10 years ($75,000).

This is simply to help you account for inflation …

If inflation averages just 4% for the next 30 years, you will need to earn $75,000 a year in retirement just to maintain the same spending power as $25,000 today!

[AJC: because everything will cost 3 times as much by 2032. Imagine: gas at $10.50 a gallon; $7.50 for a loaf of bread; etc.].

STEP 2 – Multiply by 20. Multiply your Step 1 answer by 20.

For example, if your inflated income goal was $75,000 p.a. in 30 years time, then your Number would be $1,500,000.

This is how much you would need to have saved up over 30 years, so that – in theory – you can retire on your own resources (for example, you would not need to rely on Social Security).

But, I’m guessing that even if you are earning $25,000 p.a. today, that this is not the amount you chose for Question 1.

I’m guessing that how much you really want to earn (i.e. the minimum amount that you feel would make you happy, healthy, and financially secure) is more … probably a lot more … than you are earning today.

Worse, you probably won’t want to wait 30 years to get there. I’m guessing that you want to stop needing to work (as opposed to having the financial flexibility to choose if/when you decide to work) sooner … probably a lot sooner.

[AJC: this is not true for everybody; there are plenty of people who enjoy what they’re doing so much that they cannot imagine doing anything else. This was me … until I did reach my Number and found out how much happier I could be choosing what I do – and don’t – want to work on each day.]

Plug your numbers into the above two steps and let me know (via the comments) what you come up with?

How will you get your Number?

To give you an example, I decided that my Number was $5 million and my Date (i.e. when I wanted to get there) was 5 years.

This was fairly simple to calculate: I decided that I needed $250,000 p.a. passive income (i.e. without needing to work). Since it was in just 5 years time, I didn’t bother adjusting for inflation (I could have added ~25%). Instead, I just multiplied by 20 … $5 million.

It’s pretty clear that I couldn’t save $5 million in just 5 years (after all, at that time I was still $30,000 in debt). And, it’s likely that you won’t be able to either.

[Hint: You would need to be able to save the entire amount of your desired income (Question 1.) each year for 17 years, earning at least 8% (after tax), in order to replace it in retirement.]

So, if you can’t save your way to wealth, what can you do?

It’s simple: you do two things:

1. Increase your income

There are lots of ways to do this: get a promotion; send your spouse back to work; get a second job; and so on. Necessity is the mother of invention … if you are really motivated, you will find a way.

However, my current favorite method is to start a part-time business. Why?

Well, it can grow in an unlimited fashion; it could even replace your primary income; it can create strong cashflow; if you pick the right kind of business, it can be started on your kitchen table.

My current favorite kind of part-time business is one that you can start online. Why?

Well, you don’t need much money and you probably don’t need any staff (at least, to begin). And, an online business can be so cheap to start that if you fail (and, let’s face it, you probably will) you can quickly and easily start another, and another, and …

2. Invest it all

It’s all well and good to increase your income and save as much of it (and, your current income) as possible. But, if inflation is running at just 2% (the last time I checked, it was 1.99%), and all you can get on your CD’s is 1% (Bankrate points to rates around 1.05%), then you’ve lost the ‘inflation race’ even before you’ve started.

It should be clear that it’s not enough to earn more, and save more …

… you also need to earn more on the money you save.

How much more?

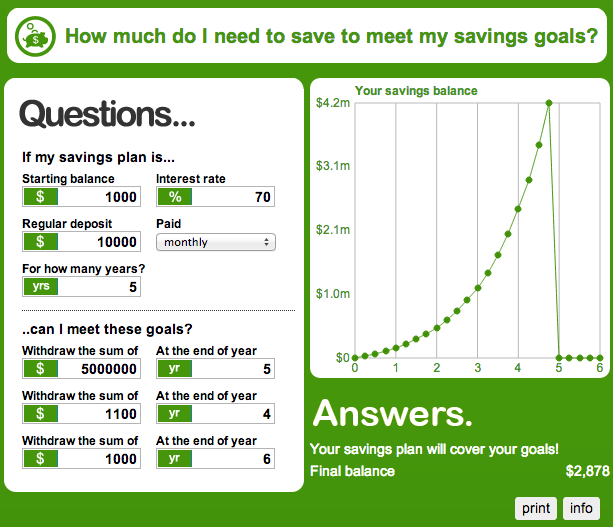

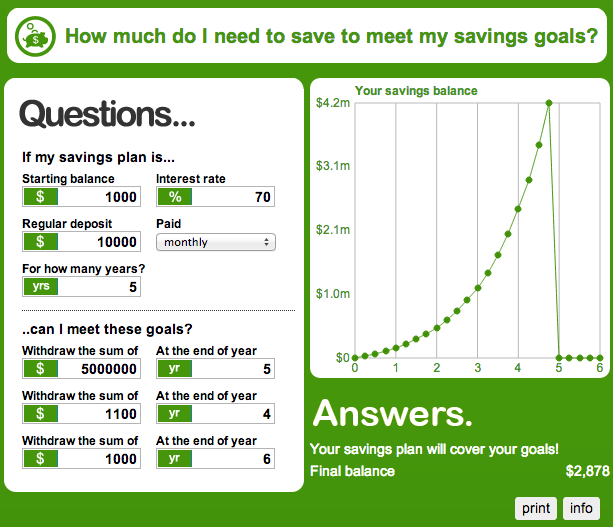

Well, that’s when you need to plug some numbers into an online ‘savings goal’ calculator:

Here’s how to make it work; plug in:

(i) How much money are you starting with?

Do you have any money in your current savings that you can tap into: CD’s; index funds; 401k; emergency fund; etc.)? In my example, even though I started $30,000 in debt, I plugged in $1,000 as the calculator doesn’t work very well with negative numbers. I could just as easily have plugged in $0, but I chose $1,000.

(ii) How much can you put aside to invest each month?

This is your current rate of savings outside of your 401k + the entire income from your side business.

This is difficult, because the amount that you might generate in monthly income will probably change over time. There’s not much you can do about this (without finding a much more sophisticated calculator or spreadsheet), so I just chose an average of $10,000 a month (or $120,000 a year) as a nice, round-figure estimate of my expected savings (driven largely by the expected profits of my part-time business).

(iii) What is your Date?

This is how long you have until you need to begin tapping into your money. I chose 5 years.

(iv) What is your Number?

This is how large your investment account needs to grow. So, I plugged in my Number of $5,000,000 and my Date of 5 years (as my end date).

Then, here’s where it gets fun: I started playing with Interest Rates to find the rough point where the calculator said that I could reach my goal (i.e. 70%). If I plugged in any figure less than 70% the calculator showed a message that said: “Oops. Your savings plan goes into the red.” … so, this was just trial and error to find the lowest number that didn’t produce this message. For me (in 5% increments) the answer came to an annual ‘interest rate’ of 70% .

That’s it!

How do I know that this works? Well, I have the benefit of hindsight 😉

But, that’s not the point: the point is to show you:

a) Not only do you need to save (a lot) more than you ever thought reasonable, but

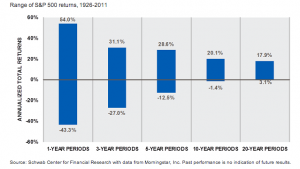

b) You also may need to earn (a lot) more on your investments than is possible with CD’s (<1% annual return, after tax) or index funds (<8% annual return, after tax).

So, this leads us to the last piece of the puzzle:

What should you invest in?

Most people invest in whatever gives them the greatest possible return (they are the risk-takers), whatever their family/friends/advisers recommend (they are the followers), or whatever they understand (they are people of habit).

Instead, I want you to consider a totally new way to choose your investments: invest in whatever investment produces the lowest rate of return that you require with the minimum risk.

This usually means comparing the ‘interest rate’ that you came up with when using the online calculator against this table:

[Source: 7 Years To 7 Figures by Michael Masterson]

So, at a 70% required interest rate, I had no choice but to start my own business (just as well, because I was already in one); but, I supplemented by heavily investing in real-estate and some stocks.

On the other hand, you may be lucky enough (because your Number is small enough; your date long enough; and/or the amount you can save monthly is large enough) to require a much lower interest rate …

… if that’s the case, you may be able to stick with your CD or Index Fund investing strategy. But, the chances are that you will need to push the envelope … a lot.

I promised in my last post that I would close this three-part series with my “strategies for real financial security”.

In this post, I showed you that the Number that means financial security is different for everybody, but I also showed you a very quick way to find yours.

That’s the starting point.

Then I showed you what kind of investment strategies you would need to follow, if you want to have any real chance of reaching your Number.

Now, it’s up to you to begin putting in place your plans to get there, starting with learning how to invest in stocks, real-estate, and/or small business.

For my part, I decided to start writing this blog (and, now my book) to help those whose required growth rate / interest rate is at the higher end of the spectrum, simply because most other blogs focus on those at the lower end.

If your required growth rate is high, as I suspect it may be, you have a huge job ahead of you …

… but, if you don’t make the effort now, go back and read these three posts and you’ll quickly realize that you’ll have an even bigger problem later.

So, keep reading, keep commenting, and keep e-mailing me with questions [ajc AT 7million7years DOT com], and I’ll do my very best to help!

There’s a Rule of Thumb that says that you should keep 100% – Your Current Age in stocks (and, the rest in bonds).

There’s a Rule of Thumb that says that you should keep 100% – Your Current Age in stocks (and, the rest in bonds).