OK, so I’ve found a few online calculators that I don’t like, but it’s time to quit bitchin’ … here’s one that I do like:

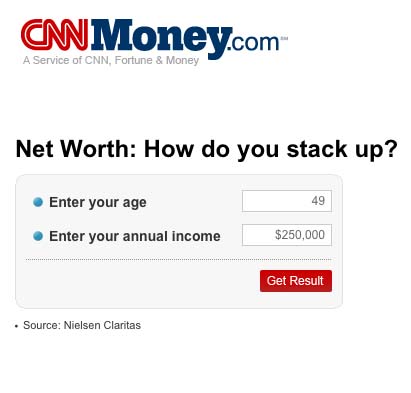

This one asks just two questions to determine how your Net Worth ‘stacks up’ against others, by age and by income.

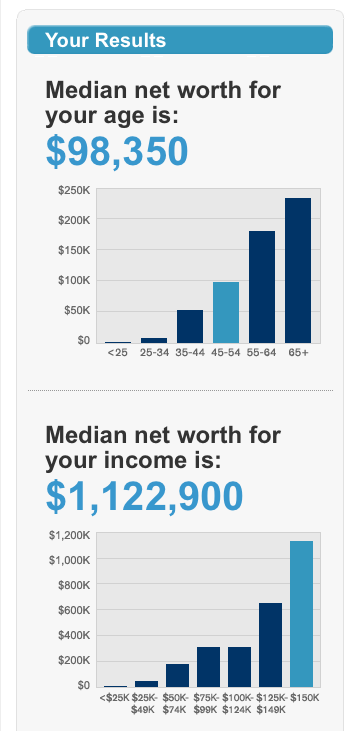

Here’s how I stacked up just before I retired (a.k.a. Life After Work) at age 49 and was still drawing a ‘salary’ of $250k:

[AJC: OK, so I’m ignoring all of my other business and investment income, etc., etc. for the purposes of this particular rant]

Again, the obvious question is: how much SHOULD I have accumulated in my net worth?

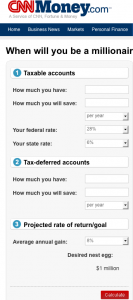

Let’s assume that I just want to replace my then-current gross income of $250,000 by the time I reach 60 … a reasonable goal, if you ask me, but still way, way more optimistic than the general population would hope for:

Step 1: $250k is roughly $385,000 by the time I reach 60 … a simple estimate of adding 50% every 10 years to allow (very roughly) for 4% inflation gets close enough to the same result without using an online calculator or spreadsheet.

Step 2: So, if I want to keep the same standard of living – with all the arguable pluses and minuses of grown up kids and greater health and insurance costs … not to mention more green fees 😉 – I’ll need to generate a passive income of at least $385k that, according to our Rule of 20 (which assumes a 5% ‘safe’ withdrawal rate), means we need $7.7 Mill. sitting in the bank (well, in something that will give us a RELIABLE 10%+ annual return).

Step 3: If I plug my starting Net Worth (let’s go for the generous starting average for people on my super-generous assumed current income) into this online annual compound growth rate calculator, I can see that I need just over a 19% average annual compound growth rate between now and then.

OK, so I have my target, now let’s take a look at how likely I am to achieve it (you see, it’s not as bad as it sounds: I can keep adding a % of my salary to my Net Worth, as well as reinvesting any investment gains and/or dividends) …

… to my mind, I’ve had 27 years of ‘practice’ to get where I am today – if I match CNN Money’s ‘profile’ – using:

– How much I had saved when I started working, and

– What % of salary I’ve managed to regularly save over those years, and

– What average investment returns I’ve managed to achieve in that time.

Well, I’ve been working for about 27 years, and I started full-time work with about $6k of car and pretty much nothing in the bank. So, if I plug in my current net worth (again, assuming that it’s what CNN Money says is ‘average’ for my super-high assumed income); what I started with; and 27 years between the two … the calculator shows that I must have averaged 21%, so no problem!

Except that I had to receive massive salary increases to get from my starting salary of $15,000 [AJC: I thought that was huge! And it was … in the early 80’s 😉 ] to my current (assumed) salary of $250,000 … in fact, my pay increases would have needed to average between 11% and 12% every year for 27 years! Now, that’s hardly likely to continue …

So, if I assume an average compounded investment return (e.g. stock market) of 12% for the past 27 years … which seems pretty darn generous, if you ask me … then, I would have needed to be smart enough to save nearly 40% of each pay packet for the entire 27 years (including putting some of it … a lot, I suspect … in my home).

Running that forward (assuming a more sedate, and probably much more likely, 5% salary increase each year until I retire at 60) and I CAN reach my Number!

In fact, I overshoot by about $1 mill., so I can even afford to drop my regular savings rate to ‘just’ 35% of my before-tax pay packet … easy, huh?!

So, it seems doable, except that I see four problems:

1. I need to have a starting salary of $250,000 per year

2. I need to have a Net Worth of at least $1.12 million by age 49

3. I need to be able to save 35% of my GROSS pay packet

4. Even after all of that, I still NEED to work until I’m 60!

[groan]

Adrian.

PS How DID I stack up at age 49? Easy: $7 million in the bank. What did I start with just 7 years before that? Nothing: I was $30k in debt. So, is it ‘doable’? Absolutely: And, this is just the place to find out how 🙂

I’m hoping that after today, you’ll never look at stocks quite the same way again … first we need to go back to when

I’m hoping that after today, you’ll never look at stocks quite the same way again … first we need to go back to when

This is rapidly appearing to become a blog about your Number … of course, that’s not the case: it’s a blog about money, specifically about how to make $7 million in 7 years, but you can pretty quickly see that having a real financial goal in mind is a powerful focusing tool.

This is rapidly appearing to become a blog about your Number … of course, that’s not the case: it’s a blog about money, specifically about how to make $7 million in 7 years, but you can pretty quickly see that having a real financial goal in mind is a powerful focusing tool. Last week

Last week