What is a stock? What is a share? Are they interchangeable, and who even cares?

Well, Debbie does … asking on the Share Your Number community forum:

I understand why you would need to have a good idea of the value of a company if you plan to buy stock in that company – But I don’t understand (and I’m sure this is stocks 101) how that translates to the price per share.

Even though this blog isn’t about Stocks 101 … there are plenty of other places on the web to find that sort of info … this does open up some interesting questions:

For example, even though I owned some of my businesses 100%, they were structured with lots of shares (usually between 100 and 1000).

Why?

Well, ‘just in case’ …

… it makes it easy for banks, partners, JV’s, partial sales, etc. to buy in – just transfer them a % of the shares: if you have 1,000 shares (or 100, it doesn’t matter … larger numbers just have more divisors and the ability to make finer and finer ‘cuts’ of the company value) and they are buying 40% of the company, you just give then 400 (or 40) shares.

Simple!

If you want to be sneaky, you create two classes of shares: A (say, 600 of the shares) and B (the rest), with the voting rights going to the A stock, which you – naturally – keep. You get to sell 40% of the company to some sucker and keep 100% of the control (actually, 60% still should give you majority control, so it’s not such a big deal, anyway)!

Unfortunately, for my New Zealand Joint Venture (fancy term for ‘partnership’), where I owned just 40% of the stock, that wasn’t possible … and, for my US JV, where I ‘controlled’ the company with 51% of the stock, there were so many “by unanimous agreement” clauses written into the shareholder’s agreement, I couldn’t blow my nose without seeking my partner’s approval, first 🙂

So, the first lesson we learn about stock is that numbers and/or percentages CAN matter less (or more) than you think … it’s all in the fine print 😉

Public companies are the same, except that they are usually (a) huge, and (b) divided into LOTS of small pieces (1,000,000+) so that people can buy very small chunks of the company, and trade them very easily i.e. for small sums of money.

These shares/stocks are traded on public stock exchanges, which are heavily regulated to make up for the fact that ‘idiots’ like me buy small pieces of businesses without the effort or forethought that they would put into buying the WHOLE business: we take all the risks without any of the business controls.

Stupid!

And, that’s why the stock market is more akin to a casino than to ‘real’ business or investing … we have no control, and only limited understanding of the underlying business that we are – in effect – buying into.

Now, here’s Josh to answer the second part of Debbie’s question (“how that translates to the price per share”):

If you think a company is worth 1 billion and there are 100 million shares outstanding, the price you think the shares are worth are 10 dollars each. Of course you want to wait until you have the opportunity to pay less then this.

So, if you would be willing – that is, if you were Warren Buffett instead of Jane Doe – to buy the whole company for $100,000,000 and it had 1,000,000 shares, then you should be willing to buy one (or each) share for $100. Except, Warren reads the financial reports and calls the shots, while we read Money Magazine and wait patiently (what other choice do we have?!) for our dividend check 😉

This leads to some other key numbers:

In a private company, we have sales and profits.

In a public company (i.e. traded on a stock exchange), we also have sales (or ‘revenue’) and profits (or ‘earnings’), but we can now also divide each of those by the number of shares available to come up with numbers like Revenue per Share and (more importantly) Earnings Per Share.

Also, if we COULD buy the whole company for $100,000,000 and it had a 25% profit margin, then for each $100 share we buy, we would expect $25 in company profits … which means the company is now selling for a Price/Earnings Ratio of 4.

Which leads me to the Grand Mystery of the Stock Market:

If a P/E of 4 is right on the money for a private company (they typically sell for 3 to 5 times annual profit/earnings) why is a P/E of, say, 15 for a publicly traded stock the ‘norm’ and a P/E of 8 to 12 times earnings so damn cheap that even Warren Buffett might buy the stock by the truckloads?!

[AJC: I know the answer … but ‘knowing’ doesn’t make it right 😉 … do you know the answer?]

So, Debbie – in case you’re worried about asking a 101 question – please remember: there’s no such thing as a bad question, only a bad answer 😛

I’m hoping that after today, you’ll never look at stocks quite the same way again … first we need to go back to when

I’m hoping that after today, you’ll never look at stocks quite the same way again … first we need to go back to when

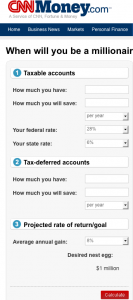

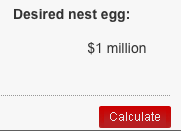

This is rapidly appearing to become a blog about your Number … of course, that’s not the case: it’s a blog about money, specifically about how to make $7 million in 7 years, but you can pretty quickly see that having a real financial goal in mind is a powerful focusing tool.

This is rapidly appearing to become a blog about your Number … of course, that’s not the case: it’s a blog about money, specifically about how to make $7 million in 7 years, but you can pretty quickly see that having a real financial goal in mind is a powerful focusing tool. Last time,

Last time,  I was just rereading

I was just rereading