About 10 years ago, my wife’s two nephews came to visit their “Uncle Adrian” to discuss potential investments.

About 10 years ago, my wife’s two nephews came to visit their “Uncle Adrian” to discuss potential investments.

They had decided to buy two apartments (in the USA, called ‘condominiums’) together – I advised them to buy one each, but they decided to go 50/50 on one, then another one a short while later.

I remember being quite proud of them, because they were both still in their early-to-mid-twenties at the time and were already investing in real-estate rather than taking the easy options of either not investing at all or speculating on stocks.

My wife’s nephews have since each married, and they each have two children under the age of 5 …

… and, they still own the two condo’s together.

I was taking one of my grand-nieces [AJC: makes me seem VERY old; I’m 53, which is only SLIGHTLY old] swimming this morning, and we got to discussing how the apartments are going.

My nephew-in-law said: “we’ve made a profit, but I don’t think they’ve been a very good investment”

Let’s examine this in a bit more detail, because I think it explains my last post quite well …

He (and, his brother) bought 2 apartments for about $200k each about 10 years ago; they are now worth about $400k each (they were worth as much as $500k each about 12 months ago, but prices have pulled back from their peak).

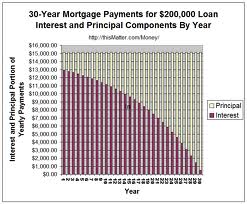

The apartments are still generating a small loss on a monthly income v costs basis, but he’s comfortable with a small level of negative gearing … and, he has an interest-only loan, so has not paid off ANY principal in the ~10 years that he’s owned 50% of each apartment.

He has calculated his return as about 7% (before tax) compounded, which I feel is pretty good but he feels that “opportunity costs” are such that he could have done a little better, elsewhere.

All in all, it doesn’t sound impressive …

… to him.

To me, the return is outstanding and explains what my last post is all about!

You see, I asked him how much (a) his loan is, and (b) how much cash he has put in so far (since the property has been making a small loss each month for 10 years).

He says that he put in a 25% initial deposit (interest-only loan), and has put (including the deposit), about $100k in cash (before tax costs/benefits).

This is how I think it breaks down (these numbers are now approximate):

– Property purchased for $200,000 (let’s assume this includes closing costs) with a 25% (i.e. $50k) deposit.

– Loan is interest only, so still stands at $150,000

– Total cash put in to date is $100,000 (made up of the $50k deposit plus another ~$50k negative-gearing losses over 10 years)

Now, let’s look at the analysis:

Cost to my Nephew-in-law:

1. $50k deposit

2. $50k losses

Profit if property sold today:

3. Property is worth $400k

4. Property purchased for $200k

5. Loan to pay off is $150k

Total Return:

6. Cash OUT is: 1. + 2. = $100k

7. Cash IN is: 3. – 5. = $250k

[AJC: notice that the price that he paid for the property doesn’t even figure – directly – into the equation; all that matters is what he owns (current value) less what he owes (current loan + the cash he puts in)]

This is no different to putting $100k in the bank (or some other investment) and getting $250k back after 10 years.

Using a compound growth rate calculator, this is a 9.5% annual compound return, not 7% as first thought!

You see, he was making the common mistake of thinking that the apartment ‘only’ doubled in value in 10 years (from $200k to $400k, which is a still amazing 7% return in today’s depressed investment climate).

But, you simply need to look at how much cash you put in, against how much cash you get back out when you eventually sell (or, you can still do this calculation on the likely selling price, if you want to keep the investment) to find your real return …

… i.e. the less cash you put in, the greater the return.

It’s usually as simple as that!

.