It is commonly taught that in order to build wealth, you first need to save; and, the best way to save – so common financial wisdom says – is to pay yourself first.

It is commonly taught that in order to build wealth, you first need to save; and, the best way to save – so common financial wisdom says – is to pay yourself first.

Investopedia (the online investment dictionary) explains Pay Yourself First:

This simple system is touted by many personal finance professionals and retirement planners as a very effective way of ensuring that individuals continue to make their chosen savings contributions month after month. It removes the temptation to skip a given month’s contribution and the risk that funds will be spent before the contribution has been made.

Regular, consistent savings contributions go a long way toward building a long-term nest egg, and some financial professionals even go so far as to call “pay yourself first” the golden rule of personal finance.

Whilst certainly better than the other 99% of the population who don’t even bother saving anything, paying yourself first doesn’t go far enough:

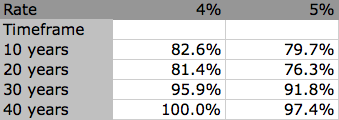

Never mind underestimating what it costs to live a reasonable lifestyle, realize that the old “retire a millionaire’ ideal is no longer adequate; this is largely because of inflation i.e. over 40 years, you will suffer roughly two doublings in the cost of living.

Another handy way to think about this is to think of your retirement date & financial target:

Think of a ‘number’ … the amount that you think is reasonable to aim for in retirement, given the financial strategies that you feel that you can employ. Can you save $1,000,000 by your expected retirement date? Less? More?

Don’t guess; there are plenty of retirement saving calculators around to help you with this task …

1. If 20 years out, ask yourself: “would I be happy with living off no more than 2% of that number, each year?”

2. If 40 years out, ask yourself: “would I be happy with living off no more than 1% of that number, each year?”

If your answer is a resounding ‘yes’ then you are done … it looks like your retirement savings strategy will work.

Congratulations!

Now, stop reading this $%@@# blog, it will make your head spin 😉

But, I’m guessing that the answer will be ‘no’ … then what?

Then, you have to face some realities about your current “pay yourself nothing” and “pay yourself first” and “no debt in my life” strategies:

– A million dollars in 20 years (= approx. $500k today) to 40 years (= approx. $250k today), is too low a target,

– 10% isn’t enough to save,

– 20 – 40 years is too long to wait,

– Your 401k – more importantly, the underlying investments – isn’t the right place for your money,

– And, you are probably under-leveraged.

Today, we’ll deal with the first issue:

If you have two reasons to save money (1. to pay down debt, and 2. to build your investment war chest), then it stands to reason that you should pay yourself twice!

But, most people pay themselves second, if at all.

From now on, I want you to concentrate on paying yourself twice … before you spend money on anything else (other than taxes and social security); here’s how:

1. Pay Yourself Once: If you currently participate in an employer-sponsored retirement plan, then you should continue to do so, and

2. Pay Yourself Twice: You should save an additional 10% of your take-home pay – for now, this can be in an ordinary savings account clearly separated from your other funds.

If you do not currently participate in an employer-sponsored retirement plan or if you and/or your employer are currently contributing less than 5% of your gross pay into your retirement account, then you need to increase your pay yourself twice target to 15% of your take-home pay.

Of course, this is easier said than done: if you had 10% of your take home pay just lying around, by definition you would already be saving it …

… in other words, you are already paying yourself twice; if not, all of your take home pay is currently spoken for!

So, let’s start slow:

Step 1 – Could you save just 1%?

Take a close look at where your money is going: do you think you could find any spending areas where you can cut back enough to allow you to save just 1% of your take home pay?

If you are already saving – but less than the 10% / 15% Pay Yourself Second target – do you think you could find any spending areas where you can cut back enough to allow you to save another 1% of your take home pay?

[AJC: No need to start at 1% if you can find ways to save more; start at (or, adding) 2% or even more, but make sure that once you start that you never turn back … be realistically aggressive in setting your Pay Yourself Second target]

Step 2 – Wait 3 months and double it!

Over the next three months, perhaps by scouring the personal finance blogs on the internet, dedicate yourself to finding ways to double your savings rate i.e. if you started at 1%, after three months you should be saving at least 2% of your take home pay. If you started at 2%, don’t take your foot off the gas … double your savings to 4% of your take home pay.

Step 3 – Repeat

Keep doubling every three months until you reach 8% of your take home pay; three months later, save that 8% plus an additional 2% of your take home pay.

Step 4 – Almost there

What you do next depends on your Pay Yourself Second target:

– if you are already saving at least 5% of your gross pay in an employer-sponsored retirement plan (or similar), then you are done! Keep saving that 10% of your take-home pay.

– if you don’t participate in a retirement plan, or if you contribute less than 5% of your gross pay (including employer contributions), then you should keep saving 8% of your take-home pay plus you should concentrate on doubling the additional 2% every 3 months (i.e. 2% to 4% to another 8%) until you reach your combined target of 15%.

Step 5 – NEVER give up

Start today and never stop!

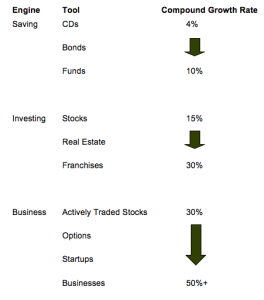

Unfortunately, as I’ve already pointed out, saving alone won’t get you to Your Number … it won’t even replace your current salary!

So, next time, I’ll help you decide what to do with your Pay Yourself Twice savings …

I met a small business owner a few weeks ago …

I met a small business owner a few weeks ago …