Motley Fool tells us about Lou Eisenberg who just seems like another Global Financial Crisis statistic: broke and living in a mobile home, supported by $250 per week in Social Security and pension payments …

Motley Fool tells us about Lou Eisenberg who just seems like another Global Financial Crisis statistic: broke and living in a mobile home, supported by $250 per week in Social Security and pension payments …

… except that in 1981 Lou “won what was, at the time, the largest-ever lottery payout”, valued at $5 Million.

Now, with the 25 year inflation rate averaging around 3.25% (at least, according to my calculations), I put that at something approaching $9.5 million 2009 dollars …

… a fortune in anybody’s language!

So, what went wrong?

A number of things: for a start, Lou didn’t actually get $5 million in cash, instead he received a 20 year ‘annuity’ of $130,000 a year after tax.

Even so, that’s $250,000 a year (for 20 years!) in today’s dollars – plenty for anybody to live a very nice lifestyle … so, what went wrong?!

The article doesn’t actually say, but I’ll take a stab:

Like most lottery winners, Lou thought that he was rich and set for life, and probably started spending like it. Big mistake!

In reality, because the money is fixed and runs out after 20 years, it’s nowhere near like having $5 million in the bank: with $5 million, you would put $250k aside and pay off your debts and have a nice holiday and buy a slightly nicer car with the change.

As for the other $4.75 million, you would buy some nice income-producing real-estate for $4.5 million – keeping $250k as a buffer against ‘problems’ – and, live off whatever 75% of the rent gives you … probably something like $225k indexed for inflation for life (and, your kids and/or charities have an inflation-protected estate worth $4.5 million in 1981 and probably around $11 million today).

Now, THAT’S rich 🙂

But, Lou didn’t get $5 million … he ‘only’ got $130,000 a year for 20 years.

So, even though he didn’t know it at the time (but, he sure knows it now that it’s too late) he wasn’t even comfortable … the lottery only gave him enough – IF he planned things well enough – to stop work and live a $65k a year lifestyle!

How can that be so?

Well, for a start, the $130k a year only lasts for 20 years then stops suddenly … so, what does Lou do then?

Secondly, the $130k a year does not increase with inflation …

…. do you begin to see the problem?

You see, Lou should be looking at:

1. What is the buying power of his FUTURE $130k today?

2. And, how much of that $130k can he replace on or before the 20 years is up with passive income?

He should always aim to live off the inflation-reduced lesser of the two.

This is not terribly different from somebody who is planning to retire in 20 years, in that Lou has to use some of his current ($130k p.a.) income to produce a nest-egg large enough to support him in real-retirement (i.e. when he stops working AND the regular ‘pay checks’ stop coming in) except that Lou:

i) Does know what his final ‘salary’ will be (i.e. $130k after tax), and

ii) Doesn’t have to actually do any real ‘work’ ever again … at least, not if he had read this post in advance 🙂

So, here’s the logic that you need to apply if you win the lottery, or even if you just plan to work for the next 20 years, and haven’t actually thought about saving or investing until now:

Step 1

Estimate your final salary i.e. $130,000 (after tax) a year in 2001

Note: You should deflation-adjust that figure into ‘today’s (i.e. 1981 for Lou) dollars. At 3.25% inflation, $67,000 would have the same buying power in 1981 as $130,000 would in 2001. In other words, if Lou didn’t want to lower his standard of living over the 20 year period of his payouts, he would need to spend something less than $130k a year from 1981 onwards.

In fact, to maintain exactly the same standard of living year-upon-year (from 1981 to 2001) he should spend only $67k a year in year one and build up to $130k by year 20, giving himself a 3.25% ‘pay-rise’ each year to keep pace with inflation.

Step 2

Decide what % of your salary that you would like to spend and what % you would like to put towards your future (i.e. when the 20 years is up and your ‘salary’ abruptly stops, or when Lou’s $130k a year checks stop rolling in). Because you can’t spend all the money in the early years, anyway (see Note above), your ability to save is kind’a built in.

I suggest starting with 30% ie that means that Lou should start by spending only 30% x $130k = $39k a year of his payout checks; this is nearly half the full $67k that $130k 2009 dollars is worth in 1981, but (in Lou’s case) is necessary to make the numbers work [AJC: as will become apparent].

Before you say that $39k is paltry, remember that this is all happening in 1981, and his self-provided ‘pay-rises’ will ensure that Lou builds up to a ‘salary’ of $95k in 2009 …

… in fact, the $39k in 1981 IS $95k in 2009: not too shabby 🙂

And, Lou hasn’t lifted a finger in over 25 years!

Step 3

Start saving the balance (i.e. the other 70% in 1981) of the yearly $130k payout check; now, this is a tidy $91k in 1981 dollars (which would be like saving nearly $223k a year, in 2009 … a VERY tidy sum).

Why spend only 30% and save as much as 70% of his payouts? Because Lou has to build his own ‘retirement fund’, he has to do it all on his own, and he has only 20 years to do it in!

Let’s put him 100% into stocks and/or mutual funds [AJC: yuk] and, to be extremely conservative, I simply used the ‘guaranteed’ 20 years stock market return of 8%, to the tune of $91k invested in the first year (1981), slowly decreasing to $56k annual “top ups” by the final year (2001).

Why reducing?

Well, Lou needs those 3.25% pay increases each year to keep up with inflation, but his $130k a year total income is fixed, so something has to give … the good news is that Lou can comfortably afford to increase his spending and decrease his savings rate, IF he plans it well and does it slowly … again at that magic 3.25% annual rate. Get it?

Step 4

With all that money going into reasonably conservative investments, over the 20 years, Lou will manage to keep ‘pay-rising’ his way to a $73k annual ‘salary’ in 2001, yet still manage to build up a $4 million nest-egg!

The Rule of 20 says that even after the lottery checks stop coming, Lou should be able to comfortably live off $200k a year (indexed for inflation for life) by way of passive income generated by his investments (i.e. by a combination of dividends and/or selling a small portion of his stock holdings every year), commencing in 2001

Step 5

Instead of giving himself a sudden ‘pay-rise’ to $200k p.a. when the lottery checks stop kicking in, and the retirement nest-egg dividend checks take over, Lou can simply iterate this model by saving less than 70% of his 1981 income, until his 2001 lottery-spending closely matches his 2002-onwards Rule of 20 nest-egg payout …

… according to my figures, this actually allows him to start by saving exactly half of his first annual $130k lottery check, and spending the other half without guilt:

That’s $65k in 1981 or an annual salary of $160k (in today’s dollars) – indexed for inflation – and, for life!

So, the secret – if there is one – is to:

a) Always think in terms of paying yourself an annual ‘salary’ (whether your windfall comes in one chunk or many), and

b) Always try and live off less than you think that you can reasonably build up in passive income by the time that you need it, and

c) Apply all the other rules that I have shared on this blog, when it comes to deciding how and when (and on what) you will spend that ‘salary’.

Of course, you can always just decide to have fun, splash your money around, and retire to your trailer park, like Lou … easy come, easy go 🙂

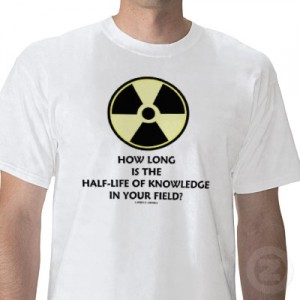

What do cars and radioactive material have in common?

What do cars and radioactive material have in common?

… well not exactly a new measure, more a new definition.

… well not exactly a new measure, more a new definition. Motley Fool tells us

Motley Fool tells us