Prior to 2008 in the USA, and still in many other countries (including Australia), residential real-estate, along with managed funds, had become one of the most favored forms of personal investment …

Prior to 2008 in the USA, and still in many other countries (including Australia), residential real-estate, along with managed funds, had become one of the most favored forms of personal investment …

… one could say the opiate of the masses, as evidenced by the huge rise and fall of residential real estate (and stock market) values across the USA in 2008 and beyond.

Jackie L, cleverly likens investing in real-estate to doing leveraged buyouts in the world of business:

Housing is generally a poor asset class. Housing’s like a leveraged buyout. You put in a little equity up front and fund the rest of the purchase with debt. The real value from housing comes when you sell the property or refinance because you’ve increased your proportion of equity ownership through mortgage payments.

The idea of creating leverage (by borrowing) in residential real-estate investments, though, isn’t so that you can pay it down (which would merely de-leverage yourself, so why do it?), it’s so that you can grab a larger chunk of upside.

You see, the promise of residential real-estate is alluring: You buy a $100k condo with $70k of the bank’s money and $30k of yours. In 10 years, the property doubles in value and you sell it for $200k, giving the bank back its $70k and pocketing $130k for yourself.

You haven’t just doubled your money in 10 years (still a healthy 7.2% compounded return), you’ve actually grown your $30k investment into $130k (in just 10 years), which is an astounding 16% compounded annual return.

If you could keep this up for another 20 years, you would have built up a $2.3m fortune.

No wonder so many people see the allure in investing in residential real-estate … which, of course, lead to the boom leading up to 2008.

The reality is a little different:

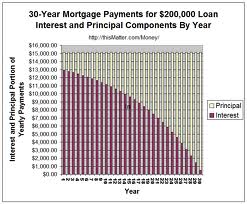

On closer examination, you begin to realize that most residential real-estate investments aren’t cash-flow positive for many years, so you have to keep pumping cash in, and there are ongoing costs: mortgage payments, vacancies, taxes, repairs and maintenance, and so on, that your rents simply can’t cover – at least not for many years.

Even so, if residential real-estate doubles in value every 10 years, it’s probably still a great long-term investment.

But, and here is the second catch, in the current market most real-estate has dropped in value. And, in most ‘normal’ markets (i.e. over the history of recorded real-estate transactions in the USA), real-estate only tends to grow with inflation … which means it doubles every 20 years rather than 10.

So, this means that you need to find residential real-estate that will grow at about twice the rate of the average piece of US real-estate, which has been doable (at least until recently) for many, many years, and will most likely be doable again in the future.

In fact, now may be a great time to find those long-term ‘bargains’.

But, the problem remains: residential real-estate is not an investment.

You are gambling short-term losses on long-term price appreciation, therefore, purchasing residential real-estate (other than to live in) is speculation.

[AJC: Commercial real-estate is another matter entirely, as its current value is determined by its current and future ability to earn an income, as I explained in this post]

Yet, I own residential real-estate, quite a lot of it … why?

Well, there are two compelling reasons why I own – and why you should own – residential real-estate:

1. To live in

I like security of tenure; that means that nobody can throw me out of my house. My house is even paid off, so I don’t have to worry about what the market does to its value, but this is a luxury that you can’t afford: you should have no more than 20% of your net worth tied up in the value of your house.

Once you have reached your Number, go ahead and pay off your house. Enjoy!

But, the real reason why you should own your own home is that, for most people, it will be the only way that you ever get off the batter’s plate when it comes to investing.

2. To protect yourself

A down-market, like now, is a great time to buy residential real-estate. When you are retired – and, can pay cash – is another time.

The reason is simple: once you realize that you are NOT going to speculate … you are NOT going to buy in the hope of a future increase in value … you are NOT going to sell, ever …

… then, you buy for one reason and one reason only:

For protected rents.

What do I mean by ‘protected rents’?

Well, residential real-estate tends not to produce the same returns as other classes of investments; that means $100k invested, for example, in commercial real-estate will produce a better rent, with fewer outgoings (costs), hence better overall returns.

However, in a ‘down market’ – worse still, depression – businesses go under leaving commercial offices, warehouses, factories, and shops vacant. And, the stock market tanks.

But, people still need somewhere to live …

So, good residential real-estate will always deliver some income. Not always great, but always some. That’s why a good chunk (but, not all) of my net worth sits in residential real-estate and, as you get closer to ‘retirement’, so should yours.

And, because residential real-estate tends to increase in value at least in line with inflation (given a reasonable time horizon), your capital is largely ‘inflation protected’, so your children should be equally happy 😉